By: Bonny Lin, Truly Tinsley, Leon Li, Brian Hart, Hugh Grant-Chapman, and Feifei Hung

October 16, 2025

Rapid modernization has enabled China to provide its citizens with improved living standards and greater economic opportunities. Over recent decades, women in China have enjoyed notable gains in areas such as life expectancy, literacy, and educational attainment.

Yet China’s progress has yielded uneven gains for men and women. The nearly 700 million women in China still experience pronounced gaps in economic opportunities, and they are severely underrepresented within Chinese politics and the military. Due to decades of population controls, China also has one of the most skewed sex ratios in the world, deepening the country’s ongoing demographic crisis. To confront demographic challenges, Chinese leaders are taking measures to encourage women to have more babies and reinforcing a rhetoric that women should return to a lifestyle centered around the home.

These realities are reflected in China’s mixed performance in the World Economic Forum’s (WEF) Gender Gap Index, which measures gender parity based on economic achievement, education, health, and political empowerment. In 2025, China ranked 103rd out of 148 countries.

Global Gender Index

Women’s Health Prospects in China

Access to healthcare is a key measure of women’s quality of life. As China has grown richer, women1 in China have enjoyed a higher life expectancy. Chinese females born in 2023 can expect to live 81 years, an increase of 6 years from 75 in 2000 and 14 years from 67 in 1980. While female life expectancy in China has surpassed the global average since 1970 and is currently equal to the United States (81 years), it still falls short of high-income neighbors like Japan (87 years) and South Korea (86 years).

Improvements in health outcomes have primarily been driven by government initiatives. In 2006, President Hu Jintao initiated comprehensive healthcare reforms to enable “everyone to enjoy basic healthcare services,” and as of 2024, an estimated 94 percent of Chinese women had basic healthcare coverage. Beijing has also instituted programs specifically designed for women. One such initiative is the National Program for Women’s Development, which started in 2001 and is now on its third iteration that will span from 2021 to 2030. This program has worked to increase access to preventive screenings, standard reproductive healthcare services, and health and nutritional education.

Such measures have delivered tangible gains. From 2009 to 2024, the healthcare system provided 342 million free cervical cancer screenings and 245 million free breast cancer screenings. Further, over RMB 3 billion (about $424 million in 2023) in central expenditure went to assisting sick women between 2012 and 2024.

Other health indicators, such as maternal mortality rates, also reflect positive trends. According to World Bank estimates, China dramatically lowered its maternal mortality ratio from 102 deaths per 100,000 live births in 1990 to only 16 per 100,000 in 2023. This ratio surpasses those found in other large developing economies like Brazil (67:100,000) and India (80:100,000). Notably, China is also marginally ahead of the average for wealthier OECD countries, which sits at 17 deaths per 100,000 live births.

China has also taken strides to improve postnatal care. A law introduced by the State Council in 2012 increased paid maternity leave to 14 weeks, and in some provinces, an entire year. The length of maternity leave in China is comparable to the paid leave offered by many wealthy European countries, and it is a significant improvement over the United States, which has no federally mandated leave.

While China has achieved a higher life expectancy and better health outcomes for women, it still suffers from one of the most imbalanced sex ratios at birth in the world, ranking 146 out of 148 countries surveyed in the 2025 WEF’s Gender Gap Report. However, this is a slight improvement from WEF’s 2021 report, in which China ranked last. The lingering effects of the One-Child Policy and the longstanding cultural “son bias” have contributed to a female to male ratio of 100:111 at birth in China. The sex ratio at birth is even more pronounced in specific areas in China. China’s 2020 census revealed that in Guangdong, for instance, the ratio was roughly 100 females for every 115 males. It should be noted, however, that this sex ratio may not tell the full story, as former population control measures led to some families hiding their female children at birth in order to have more than one child.

Decades of a highly imbalanced sex ratio have left China with a large population of young unmarried men. There were 30 million more men than women in China in 2024, many of whom could be single for life. Further, China is now facing a dual demographic challenge of a rapidly aging population and a decreasing number of newborns.

In response to the demographic crisis, the government is actively deploying propaganda to push women to have more children. In recent years, Chinese leader Xi Jinping has started to heavily reinforce traditional family values, specifically the importance of women’s role as a mother and caretaker.

Significant demographic shifts present China with mounting social challenges. Learn more about how China’s demographic challenges compare to other countries around the world.

Material incentives are also underway. Under the One-Child Policy, the Chinese government fined families for having a second child; in 2025, China introduced a childcare subsidies program, which offers families RMB 3,600 per year ($509 in 2023) for each child under the age of three. However, many view these government checks as insufficient. According to a Chinese population research group, the average cost of raising a child from birth to age 18 in China has risen to 6.3 times China’s GDP per capita—making China one of the most expensive countries to raise a child.

Another issue that continues to disadvantage women’s physical and mental health in China is intimate partner violence. In December 2016, China enacted its first domestic violence law, which prohibits any form of domestic violence and outlines reporting and safety mechanisms for victims and witnesses. According to official reporting, an estimated 8.6 percent of married women experienced domestic violence in China in 2021, a decrease from 13.8 percent in 2010. Notably, 2023 OECD estimates suggest that China’s rate of intimate partner violence is lower than India, the United States, Japan, and the average of OECD countries.

However, these statistics may not tell the full story in China. Many instances of domestic violence may go unreported, and in practice, the 2016 law is often ineffective in protecting victims. This stems from the Chinese state’s tendency to promote family integrity over women’s safety in an effort to preserve social stability. Studies show that Chinese courts often dismiss women’s claims of abuse and violence in favor of keeping the marriage intact. This follows the Chinese leadership’s decades-long emphasis that harmonious families lead to a harmonious society. This sentiment results in law enforcement being discouraged from interfering in what they view as family disputes and, in turn, prevents them from providing effective protection to the abused. Instead, Chinese police frequently opt to give verbal warnings to perpetrators of domestic violence rather than more severe punishments, which leaves victims in dangerous environments with limited options for safety. Almost 100,000 of these warnings were issued in 2023.

Women’s Access to Education in China

Education is a critical factor in social equality and mobility. China has made a concerted effort to boost access to education for its entire population. The 1986 Nine-Year Compulsory Education Law and the 1995 Education Law of the People’s Republic of China established equal access to enrollment, degree programs, and study abroad programs. These measures have contributed to a rise in the literacy rate of women from 86.5 percent in 2000 to 95 percent in 2020, slightly higher than female literacy rates in other upper middle-income countries (94 percent in 2020). While noteworthy, female literacy in China still lags behind male literacy (98 percent in 2020).

The mean years of schooling for women in China has also improved, from 3.7 years in 1990 to 7.8 in 2023, yet it still falls short of the male average at 8.3 years. The vast majority of young Chinese women (96.2 percent in 2020) move on to secondary schools, and the female gross enrollment ratio for primary and secondary school reached 97.1 percent in 2021, higher than the male ratio at 95 percent. Since 2008, Chinese women have also been more likely than men to continue onto tertiary and postgraduate education. Notably, the WEF ranks China as number one in gender balance for tertiary education in 2025, with women enrolling at a 11.47 percent higher rate than men.

However, China’s top universities still tend to enroll significantly more men than women. In 2022, the female to male ratio at Peking University, one of China’s most prestigious universities, was 46 to 54, while the ratio at Tsinghua University was lower at 34 to 66.

China’s urban-rural disparities further affect equal access to education. A 2016 report by the China Social Welfare Foundation found that while 96.1 percent of rural girls had enrolled in primary education, only 79.3 percent moved on to secondary levels. Some note that this drop is due to lower parental expectations and fewer employment opportunities for rural women.

Beijing is working to reduce the gap between rural and urban girls. In poorer provinces like Sichuan, Ningxia, and Gansu, local governments have invested in improving school infrastructure, including multimedia learning and livestreamed lessons to allow resource-sharing between urban and rural students. In 2021, the Chinese central government also released a 10-year development plan that included goals to boost women’s education attainment, with specific plans to ensure education access for rural girls.

Economic Opportunities for Women in China

China’s economic growth has improved overall prosperity, but Chinese women have benefited less from these gains. Throughout the 1980s, female participation in the labor force was high, averaging around 80 percent. However, that percentage has slowly dropped over time, and in 2024, female workforce participation in China was only 59.6 percent while male participation was at 71.1 percent. Still, China’s female participation rate is slightly higher than several other major economies, such as the United States (56.5 percent) and Japan (55.3 percent).

China’s changing social and demographic structure and economic modernization are commonly cited as primary factors for this decline. In particular, the restructuring of China’s state-owned enterprises in the 1990s had particularly negative consequences for women. Privatization measures aimed at boosting productivity and efficiency precipitated layoffs of low-skilled, and often female, workers.

China’s development has also disproportionately benefited men. In 2023, Chinese women earned roughly $11,000 less than men, a 41 percent gap.2 This marks a widening income gap from 34.7 percent in 1990. Nonetheless, China’s wage equality fares better than many other major economies. The 2025 WEF report ranks China 31st globally in wage equality, in front of the United States at 40th, the UK at 54th, Japan at 93rd, and South Korea at 94th. Ranked in the bottom fourth globally in terms of wage equality, South Korean women earned $22,750 less than men in 2023.3

China also has a noticeable lack of women in corporate leadership positions. According to the WEF’s 2021 report, about 17 percent of senior managers, officials, and legislators in China are women. However, the noticeable absence of women leaders is not unique to China, with Japan at 15 percent and South Korea close to 16 percent.

Within China’s central state-owned enterprises (SOEs), which are some of the most powerful economic actors in China, there is an even more pronounced lack of female executives. According to CSIS China Power Project estimates, women held an estimated 8 percent of all senior executive positions within central SOEs as of August 2025.4 These disparities become even more evident when considering relative seniority. Only 3.1 percent of central SOEs had a woman chairing their board, and only 6.7 percent had a woman as their managing director or chief executive officer.

Additional roadblocks perpetuate these inequalities. For instance, China implemented a new policy in 2025 to gradually raise the retirement age. However, even with this change, the official retirement age for women remains five to eight years earlier than men, which reduces potential total earnings for women and blocks them from reaching more senior positions.

Discrimination extends to the hiring process as well. According to Human Rights Watch, 11 percent of the Chinese national civil service jobs posted in 2020 included a preference or requirement for male applicants, while less than 1 percent specifically requested women. The postings used “frequent overtime work,” “heavy workload,” and “frequent travel” as reasons why the job may not be suitable for women.

However, the government has made some efforts to decrease areas of discrimination for women in the workplace. In 2023, China’s National People’s Congress Standing Committee revised the Women’s Rights and Interests Protections Law for the first time in 15 years. The new provisions ban withholding advancement based on marriage, pregnancy, or parental status, as well as the practice of including pregnancy tests as part of pre-employment physicals.

Women also contribute extensively to the economy in China through care work in the home. Estimates vary on the value of this unpaid care work to the economy, but it ranges from 25 to 45 percent of GDP. However, women disproportionately bear the burden of this unpaid labor compared to men. According to a report by UN Women and the International Labour Organization, women spend 2.5 times as much time on unpaid care work as men in China. Additionally, in 2018, married women conducted housework for 121 minutes longer per day than unmarried women.

These trends are compounded by the fact that the Chinese government is making it harder for women in China to get divorced. In 2021, China instituted a mandatory “cooling-off period” for married couples seeking a divorce. This entails the couple taking a month-long period to reconsider the decision to get a divorce. If one party decides to back out of the divorce, the other party has to either restart the process or sue to get a divorce. This is another way in which the government tries to preserve state stability through enforcing family unity and traditional family structures.

The Chinese government, however, is pursuing efforts to level out the division of labor within the home. One such effort is the Chinese Women’s Development Program (2021-2030), which encourages couples to coordinate and divide household labor, responsibilities of caring for and accompanying children and the elderly, educating children, and managing household chores.

Women’s Political and Military Participation in China

China’s constitution guarantees women “equal rights with men in all spheres of life,” mandating the state to implement equal pay for equal work by men and women, and to train and select female officials. However, women are severely underrepresented politically.

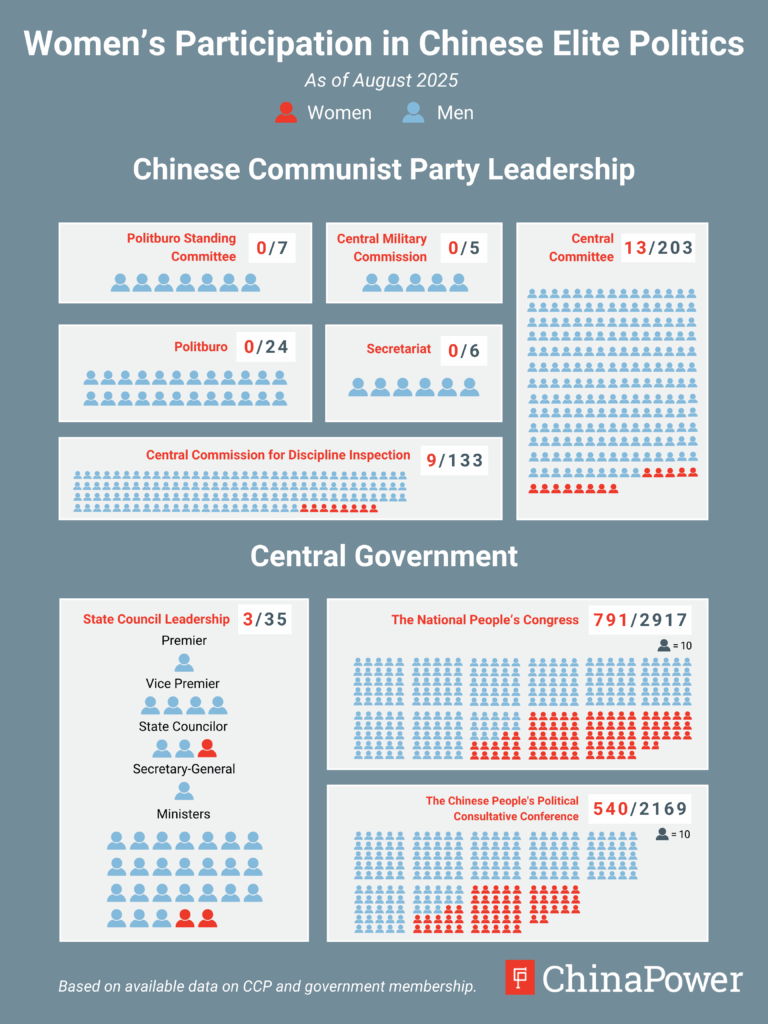

The WEF ranks China 111th in terms of women’s participation in the political system, below the United States (55th) and India (69th) but above Japan (125th).

China’s lack of representation of women in politics is highly apparent in top political decision-making bodies like the twenty-four-member Politburo of the CCP. Since 1949, China has only had six female Politburo members. The Politburo of the 20th Central Committee of the CCP (2022-2027) departed from the two-decade norm of having at least one female Politburo member and has none. No woman has ever sat on the CCP’s Politburo Standing Committee, China’s most elite political decision-making body, nor has any woman sat on the Central Military Commission, which commands China’s armed forces. As of August 2025, only 13 of the total 203 members of the CCP Central Committee were women.

Women’s membership in the Chinese Communist Party at large also remains limited, albeit improving. In 2024, females accounted for 31 percent of total party membership, compared to 19 percent in 2004.

The dearth of female party cadres systematically constrains the number of females who can rise through the ranks to attain senior positions. As of August 2025, women occupy two of the 26 ministerial positions in the central government, three of the 31 provincial-level governor positions—in Sichuan, Heilongjiang, and Inner Mongolia—and none of the 31 provincial-level party secretary positions (the de facto most influential political leader in a province). Only four women have ever risen to become provincial-level party secretaries since 1949.

Women’s presence in the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) is even more diminished, accounting for only 3.8 percent of all active-duty military personnel in 2020. Comparatively, in the United States, 17.2 percent of all active-duty military personnel were female in 2020. While total PLA active personnel decreased by 20 percent from 2000 to 2020, the number of female active personnel shrank by 43.6 percent. Furthermore, there has never been a female PLA general, and only two females have ever risen to the rank of lieutenant general. Reportedly, only eight female major generals are currently serving, and no female holds a senior position in any of the five theater commands or in the various PLA service branches.

Women’s Movements and Activism in China

As China developed and women’s access to education increased, growing awareness of gender inequity in China has also risen. However, discourse on women’s status is not new in Chinese society. Mao Zedong, founder of modern communist China, advocated for equal roles for men and women. He famously stated, “women hold up half the sky,” and established March 8th as a national holiday in China to celebrate women. This discourse helped mobilize millions of women into the workforce, primarily on collective farms and in factories.

However, China’s decollectivization and return to the household economy in the late 1970s effectively restored the traditional gender division of labor in rural China, while the One-Child Policy imposed enormous pressure on urban women’s reproductive rights. Losing faith in the state, women began to leverage channels—including spontaneous activism, non-government organizations (NGOs), media campaigns, and lawsuits—to demand state recognition of women’s struggles and speak up against sexual harassment and domestic violence.

But with Xi Jinping’s rise to power in 2012, many of the voices and campaigns advocating for an improved status for women have been silenced. The 2015 arrest of the Feminist Five (女权五姐妹), a group of five Chinese women activists, for planning to hand out anti-sexual harassment stickers on public transportation, is often cited as a turning point for the feminist movement in China. Following the arrest, Xi’s government began a systematic assault on feminist and human rights NGOs in China. In 2017, China passed a law that effectively cut off funding to most NGOs in China, including those that advocate for equality or offer legal aid and protection against sexual harassment and domestic violence.

Gender Inequality in China: A Conversation with Leta Hong Fincher

Xi’s crackdown is widely seen as an effort to preserve state stability and shift the narrative on the woman’s role back to one associated primarily with family and the home. At the 13th National Women’s Congress in 2023, Xi made this sentiment clear, stating “we should actively foster a new type of marriage and childbearing culture.” This effort has led to activists in China being forced to balance between continuing to carefully advocate for equality and ensuring they don’t raise alarms with the state.

Given this environment, feminist movements have largely been scaled back or halted, and the majority take place as micro movements by individuals online. In 2018, Chinese women began campaigning against sexual abuses and exploitation in universities and workplaces, sparking China’s “Me Too” (米兔) movement. Despite initial success, the movement was ultimately met with swift censorship. China’s popular microblogging website, Weibo, removed its hashtags for the movement shortly after they gained traction online, inspiring netizens to use puns and acronyms to prolong the online discussion. Additionally, Huang Xueqin, a prominent activist with the Me Too movement, was detained in 2021 by authorities for supposedly inciting subversion of state power.

Some women have found ways around the restrictions. For instance, a concept known as “pink feminism” has begun to gain more attention in China since 2020. This concept comes from the idea that some feminists in China may be using nationalist (“pink”) discourse alongside their dialogue on gender equality as one way to sandwich their feminist discourse and to appear less provocative to the state. There is also a tendency for activists to focus on highlighting “softer” topics related to women, such as achievements of women in sports, rather than topics that may be deemed more controversial.

Finally, some women are adopting a method of silent protest in the form of postponing or outright foregoing marriage and pregnancy. According to China’s Ministry of Civil Affairs, in 2024, China had 6.1 million marriage registrations, a decrease of 20.5 percent from 2023. This poses enormous challenges for the Chinese government as it seeks to battle its rising demographic challenges, and could be seen as an avenue for women to stand up for their rights in a way that is harder for the state to control.

Conclusion

The status of women in China is a mixed bag, and in some ways, China’s progress on improving the prospects for women in China is stalled or reversing. In areas such as levels of education, life expectancy, and labor force participation, Chinese women have made significant progress and now even fare better than high-income countries like the United States. In other areas such as roles in the military and political participation, Chinese women still face significant barriers and lag far behind their male counterparts. China’s efforts to fix its demographic crisis have also led to significant setbacks in progress for women, as Xi and the CCP promote traditional patriarchal ideology to encourage women to return to their role as primarily mothers and caretakers in the household.