On March 5, 2024, at the annual convening of the government’s “two sessions,” China released a new government budget report that will play a major role in shaping the trajectory of the world’s second-largest economy. Beijing also released new data on spending in 2023, which provides valuable insights into the country’s evolving spending priorities and its overall fiscal situation. Yet these budgets can be difficult to parse, and the topline figures only tell part of the story. This ChinaPower feature untangles the details behind China’s government budget.

View Chinese versions: 简体 / 繁體

China’s 2024 General Public Budget

At the heart of China’s government budget is the general public budget. It includes revenue and spending by the central government and local governments, as well as transfers from the central government to local governments. The 2024 general public budget projects revenue of RMB 24.5 trillion ($3.4 trillion), a 4.8 percent increase from the previous year. Expenditure is set at RMB 28.5 trillion ($4 trillion), a 1 percent increase, leaving China with an official projected deficit of nearly RMB 4.1 trillion ($564.9 billion), down 16.8 percent from 2023.1

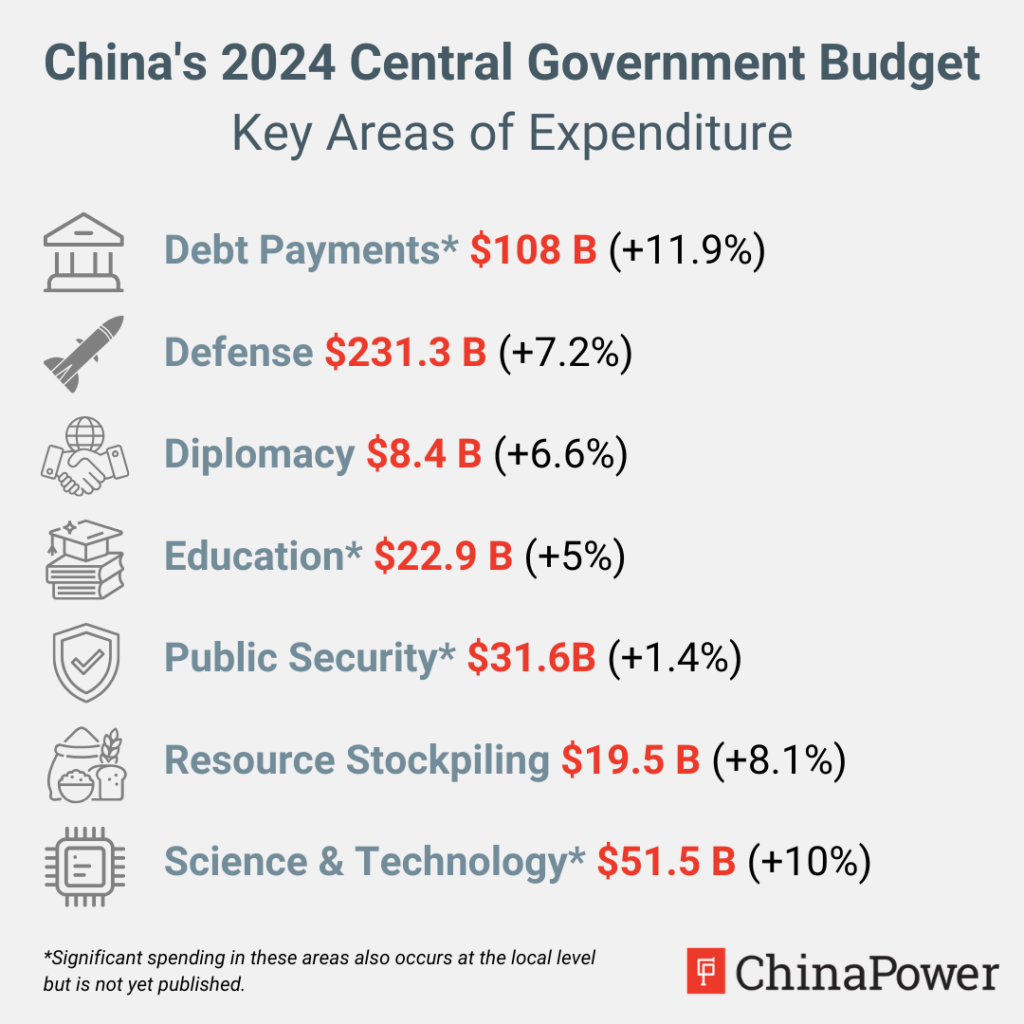

The 2024 budget does not include a detailed breakdown of spending across categories at the national (全国) level. It only provides a limited breakdown of a handful of categories at the central (中央) level, including foreign affairs, defense, public security, education, science and technology, stockpiling of grains and other materials, and interest on debt payments. These figures only provide part of the full picture since the lion’s share of spending in most of these categories takes place at the local (地方) level.

A notable exception to this is the defense budget, since virtually all spending on the military occurs at the central level, not the local level. China’s 2024 defense budget was set at RMB 1.7 trillion ($231 billion), a nominal 7.2 percent increase from the 2023 budget of RMB 1.6 trillion ($224.8 billion). This continues a recent trend that has seen nominal yearly percentage increases in the upper single digits.

Even with steady increases, China still spends less on defense than the United States. In fiscal year 2024, the U.S. Congress authorized $874.2 billion in total defense spending, which includes funding for not just the Department of Defense, but other defense-related areas.2 While China lags behind the United States in terms of defense spending, China boasts the world’s second largest military budget and continues to widen its lead over other countries. Additionally, China’s official defense figures do not capture total spending on the military. Actual defense spending is estimated to be considerably higher.

China's 2023 Fiscal Situation

In addition to laying out spending figures for 2024, the budget report released on March 5 provides preliminary data on 2023 actual spending. In 2023, China’s national general public budget revenue reached RMB 23.4 trillion ($3.3 trillion) and expenditure grew to RMB 28.2 trillion ($4 trillion), resulting in an official deficit of RMB 4.9 trillion ($690 billion).3

Both the expenditure and deficit were notably larger than in recent years, due to a rare mid-year injection of additional deficits. In response to China’s significant economic slowdown, Beijing authorized an additional RMB 1 trillion ($141.4 billion) in sovereign bonds to support the operations of local governments, specifically for disaster relief and prevention. The funds were divided in half, with RMB 500 billion ($70.7 billion) allocated for use in 2023 and the remaining funds to be carried over to 2024.

There were also several notable trends in spending in 2023. After years of declining budgets, foreign affairs spending increased significantly, from RMB 49.4 billion ($7.3 billion) in 2022 to RMB 57 billion ($8.1 billion) in 2023. China also stepped up investments in science and technology, increasing its spending by nearly 8 percent in 2023, doubling the year-on-year growth in 2022.

Spending on health and sanitation stabilized in 2023 and was the only major area to drop, falling 0.6 percent. This decrease does not necessarily indicate a cutback on spending, but instead reflects the fact that spending on health and sanitation was at a record high during the previous year’s Covid-19 lockdowns. In 2022, those lockdowns drove up spending on health and sanitation by 17.7 percent—more than double the rate of increase of any other budget category.

China's 2022 Fiscal Situation (Click to expand)

Below is a summary of China's fiscal situation in 2022.

In 2022, China faced significant fiscal constraints amid an economic slowdown and the heavy burden of China’s strict zero-Covid policies, which have since been lifted. China’s largest source of government revenue, value-added taxes, dropped by 23.3 percent from the previous year. This stemmed from tax rebates that were put in place to support Chinese businesses in the face of weak domestic spending and sluggish economic growth. Revenue from taxes on property deeds likewise came in 22 percent below 2021 totals, and taxes on land value appreciation dropped 7.9 percent due to a slowdown in China’s property market.4

These declines were partially offset by increases in other categories, including a 20.3 percent increase in revenue from consumption taxes, which are imposed on certain luxury or environmentally-damaging products such as some cars, cigarettes, and alcoholic beverages. In all, tax revenue in the general public budget was down 3.5 percent—a decrease of about RMB 612.2 billion ($90.9 billion) from the previous year.

While revenue fell, government spending on health and sanitation surged in 2022 as local governments were forced to pay for Covid-19 testing and other efforts to fight the spread of the virus. Total spending on health and sanitation was up 17.7 percent over the previous year—more than double the rate of increase of any other category. That is also notably higher than the 15.3 percent increase seen in 2020 as China faced the initial outbreak of the virus.

China’s increased health spending during the pandemic is mirrored by other countries that took substantial measures to limit the spread of Covid-19. In Australia, which implemented a series of extended lockdowns throughout 2021 and 2022, spending on health goods and services grew by 7.1 percent, which is more than double Australia’s average annual growth rate on health expenditure.

High spending in one area requires making tradeoffs in other areas. Despite Beijing’s concerted efforts to promote developments in science and technology, government spending in this area rose only 3.8 percent in 2022—well below the pre-pandemic average. Some categories even saw spending slashed in 2022. Energy and environmental protection was hardest hit among the categories listed, with a 2 percent decrease from the previous year. Expenditure on culture, tourism, sports, and media (which are categorized together) also fell by 1.8 percent, and spending on urban and rural community development dropped 0.2 percent.

Long-Term Trends under Xi Jinping

The release of 2023 data provides a more complete picture of how China’s government budget has evolved during the 11 years that Xi Jinping has been China’s leader. Buoyed by China’s rapid economic growth, the general public budget has ballooned significantly since Xi came to power in 2013. From 2013 to 2023, total expenditure grew 95.8 percent and revenue expanded 80.8 percent.

As spending has outpaced revenue each year, China has been left with a widening government deficit. In 2023 the official general public budget deficit reached RMB 4.88 trillion ($690 billion)—the highest level recorded in the general public budget.

Not all parts of the budget have grown at the same pace. Between 2013 and 2023, spending on debt interest payments skyrocketed 287 percent, faster than any other major budget category. The increase reflects the growing strain China is coming under as it grapples with rising debt. China is by no means alone in this. In fiscal year 2023, 10.7 percent of U.S. government outlays were towards interest payments on debt, and 25 percent of Japan’s fiscal year 2024 budget is expected to be spent on debt servicing.

China’s spending on social issues has also risen substantially. Expenditure on social security and employment—one of China’s largest spending categories—rose 175 percent between 2013 and 2023. China nevertheless continues to lack the robust levels of social welfare support seen in many advanced economies.

Other categories, such as science and technology and defense, have also experienced high rates of growth over the last decade. Both have been major priorities under Xi Jinping. China’s high spending on science and technology has helped to fuel major national projects such as the Chinese Space Station, the core module of which was initially lofted into orbit in 2021. Since becoming operational in 2022, China has announced plans to expand the station from three modules to six. Spending on defense has also risen at a fast clip amid a major push to modernize the People’s Liberation Army.

Some categories have lagged in comparison. Spending on foreign affairs increased just 60.3 percent over the 2013-2023 period—just over half as fast as spending on defense. Amid belt-tightening during the Covid-19 pandemic, spending on foreign affairs dropped nearly 17 percent in 2020 before dropping further in 2021 and 2022. Notably, however, spending on foreign affairs rebounded somewhat in 2023 with an increase of over 16 percent.5

At first glance, the budget figures also seem to suggest sluggish growth in spending on transportation, but it is important to note that this does not reflect total spending on infrastructure. China has spent heavily on infrastructure in recent years, in part as a means of spurring economic growth. Much of this spending is obfuscated in various parts of local government budgets. For example, China has issued special sovereign bonds to help local governments fund infrastructure and other projects. Unlike regular government spending, these bonds are earmarked for specific projects and are not reflected in the general public budget.

China’s Other Budgets

The general public budget is important, but it only tells part of the story. China has three additional national budgets: the government funds budget, the state capital operations budget, and the social insurance fund budget. In 2014, China’s Budget Law was revised to include a stipulation that revenues and expenditures from all four budgets should be included to create a “full-caliber” budget. Each of these budgets contains different components of China’s fiscal portfolio, as outlined below:

- Government Funds Budget: This budget largely falls under the purview of local governments. Revenue is primarily financed through land sales, with additional revenue from central and local governments purchases of special bonds. Expenditure flows are focused on capital expenditures such as infrastructure projects. In 2024, this budget’s revenue is projected to be RMB 7.08 trillion ($983.4 billion) and expenditure will be RMB 12.02 trillion ($1.67 trillion), resulting in a deficit of RMB 5 trillion ($686 billion). In an effort to promote economic growth, the central government will issue RMB 1 trillion ($139 trillion) of ultra long-term special government bonds for large-scale infrastructure projects that support China’s development. The entirety of these bonds will be issued to the government funds budget.

- State Capital Operations Budget: The state capital operations budget is managed by the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission and centers on the revenue and expenditure associated with China’s sprawling network of state-owned enterprises. In 2024, the state capital operations budget is projected to bring in revenue of RMB 592.5 billion ($82.3 billion) and its expenditure will stand at RMB 328.2 billion ($45.6 billion). With an additional RMB 10.7 billion ($1.5 billion) carried over from the previous year, there will be a resulting surplus of RMB 275 billion ($38.2 billion), all of which will be transferred to the general public budget.

- Social Insurance Fund Budget: The social insurance fund is managed by the National Council for Social Security Fund and is dedicated to meeting China’s social security needs. Income is generated from a subset of funds and the bulk of this is spent on costs related to pensions and medical insurance. In 2024, this budget’s revenue is projected to reach RMB 11.7 trillion ($1.6 trillion) and the expenditure will be RMB 10.7 trillion ($1.5 trillion), resulting in a surplus of RMB 1.1 trillion ($148.2 billion), which will be added to the fund’s overall capital.

With the exception of the social insurance budget (which operates somewhat separately), the Chinese government has utilized transfers across these budgets to offset deficits in other areas. China states that its official general public budget deficit in 2024 will be RMB 4.06 trillion ($563.9 billion), but without transfers from other areas, the actual general budget deficit would total RMB 10.8 trillion ($1.5 trillion).

When transfers between budgets are removed and China’s various budgets are consolidated into one total budget (excluding the social insurance fund budget), China’s fiscal situation appears significantly less healthy. China’s official 2024 deficit of RMB 4.06 trillion amounts to approximately 3 percent of China’s GDP. When the other budgets are accounted for, China’s total deficit climbs to 8 percent of GDP.

Tracked over time, it paints a picture of a rapidly worsening fiscal situation for China. In the past, surpluses in the government funds budget and state capital operations budget typically helped to offset deficits in the general public budget, but this changed significantly in 2020 as China spent heavily to offset the economic fallout from the Covid-19 pandemic.

One key part of this has been the issuance of trillions of RMB worth of special purpose bonds. These fall under the government fund budget and were primarily created as a new vehicle for local governments to raise money for infrastructure projects and other special needs. Since 2020, China has authorized the issuance of between RMB 3.65 trillion and RMB 3.9 trillion of these bonds each year.

Since 2022, China’s fiscal woes have been compounded by a major slowdown in the country’s sprawling real estate sector. Land sales are a crucial source of revenue for many local governments. Data from China’s National Bureau of Statistics show that the steep drop in land sales in 2022 stabilized somewhat in 2023, but still, declining land sales led to a 9.2 percent drop in revenue within the government fund budget.

China is not alone in facing a tough fiscal environment. Governments around the world have been challenged by the pandemic and the ensuing economic fallout. Yet China’s situation is worsening at a rapid pace. If its deficits continue to grow, Chinese leaders will be forced to grapple with increasingly tough decisions about how to increase revenue or cut spending—or both.

Authors:

Brian Hart, Bonny Lin, Matthew P. Funaiole, Samantha Lu, Hannah Price, Matthew Slade