Updated: October 21, 2025

Many worry that China’s ownership of U.S. debt affords China economic leverage over the United States. This apprehension, however, stems from a misunderstanding of sovereign debt and of how states derive power from their economic relations. The purchasing of sovereign debt by foreign countries is a normal transaction that serves several legitimate economic policy goals. Consequently, China’s stake in U.S. debt has more of a binding than a dividing effect on bilateral relations between the two countries.

Even if China wished to “call in” its loans, the use of credit as a coercive measure is complicated and often heavily constrained. A creditor can only dictate terms for the debtor country if that debtor has no other options, but U.S. debt is a widely held and extremely desirable asset in the global economy. Whatever debt China does sell is likely to be simply purchased by other countries. In fact, China’s known holdings of U.S. debt have gradually declined after peaking in the mid-2010s, and Japan and the United Kingdom have overtaken China as the top holders of U.S. debt.

Furthermore, China needs to maintain significant reserves of U.S. debt to manage the exchange rate of the renminbi. Were China to suddenly unload its reserve holdings, its currency’s exchange rate would rise, making Chinese exports more expensive in foreign markets. As such, China’s holdings of U.S. debt do not provide China with undue economic influence over the United States.

Why do countries accumulate foreign exchange reserves?

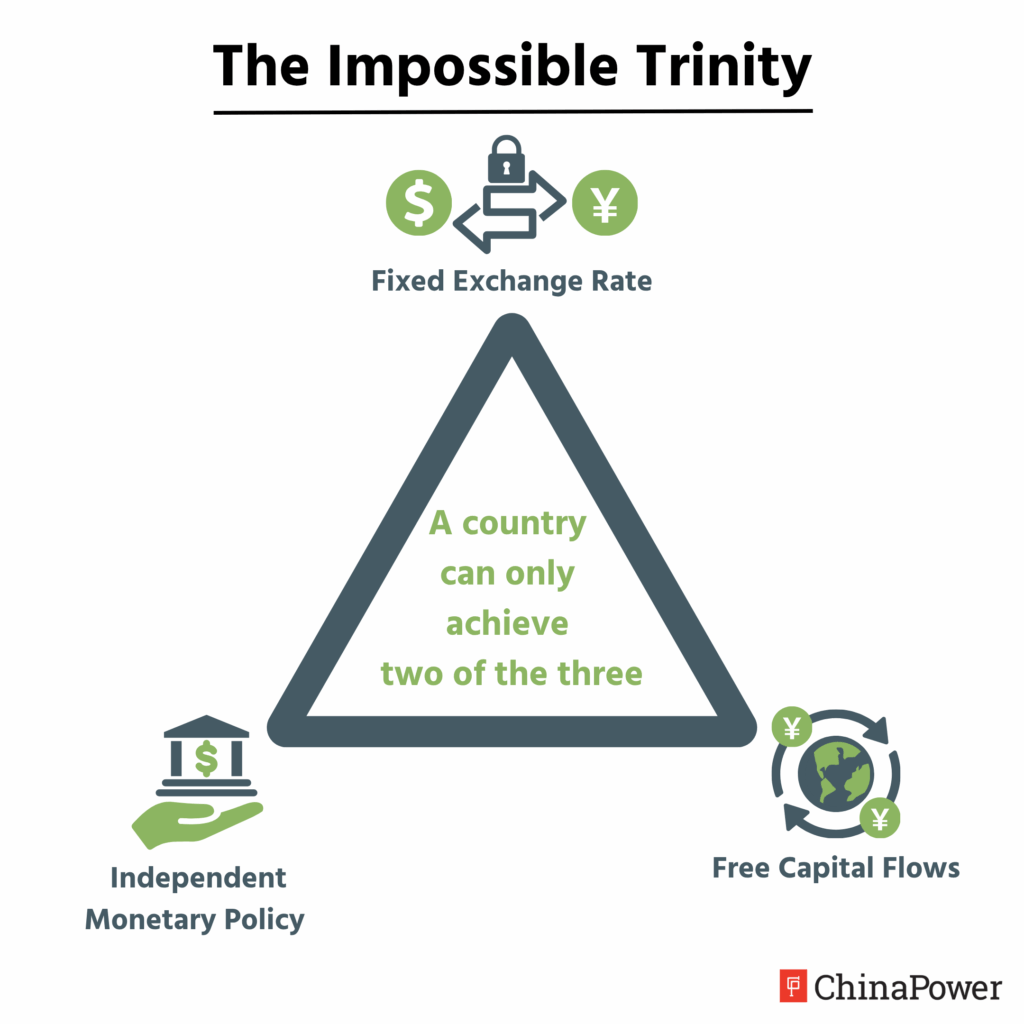

Any country that trades openly with other countries is likely to buy foreign sovereign debt. In terms of economic policy, a country can have any two—but not three—of the following: a fixed exchange rate, an independent monetary policy, and free capital flows. Foreign sovereign debt provide countries with a means to pursue their economic objectives.

For instance, China manages the exchange rate of the renminbi and it maintains an independent monetary policy, but to achieve that, it cannot allow capital to freely flow in and out of its economy. The United States has an independent monetary policy and allows capital to freely flow through the economy, but Washington does not directly manage the value the U.S. dollar’s exchange rate.

Owning foreign sovereign debt provides countries with a means to pursue the objectives of their respective monetary and trade policies. Specifically, it helps to achieve three main objectives. First, countries can hold sovereign debt as part of their foreign exchange reserves to facilitate trade. Second, central banks buy sovereign debt to maintain their currency’s exchange rate or forestall economic instability. Third, as a low-risk store of value, sovereign debt can be an attractive investment asset to central banks and other financial actors. Each of these functions is discussed briefly.

Foreign Reserves

Any country open to international trade or investment requires a certain amount of foreign currency on hand to pay for foreign goods or investments abroad. As a result, many countries keep foreign currency in reserve to pay for these expenses, which cushions the economy from sudden changes in international investment. Domestic economic policies often require central banks to maintain a reserve adequacy ratio of foreign exchange and other reserves for short-term external debt, and to ensure a country’s ability to service its external short-term debt in a crisis. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) publishes guidelines to assist governments in calculating appropriate levels of foreign exchange reserves given their economic conditions.

Exchange rate

A fixed or pegged exchange rate is a monetary policy decision. This decision attempts to minimize the price instability that accompanies volatile capital flows. Such conditions are especially apparent in emerging markets: Argentinian import price increases of up to 30 percent in 2013 led opposition leaders to describe wages as “water running through your fingers.” Since price volatility is economically and politically destabilizing, policymakers manage exchange rates to mitigate change. Internationally, few countries’ exchange rates are completely “floating,” or determined by currency markets. To manage domestic currency rates, a country might choose to purchase foreign assets and store them for the future, when the currency might depreciate too quickly.

A low-risk store of value

As sovereign debt is government-backed, private and public financial institutions view it as a low-risk asset with a high chance of repayment. Some government bonds are seen as riskier than others. A country’s external debt may be viewed as unsustainable relative to its GDP or its reserves, or a country could otherwise default on its debt. Generally, however, sovereign debt is more likely to return value and therefore is safer relative to other forms of investment, even if earned interest is not high.

Why does China buy U.S. debt?

China buys U.S. debt for the same reasons other countries buy U.S. debt, with two caveats. The crippling 1997 Asian Financial Crisis prompted Asian economies, including China, to build up foreign exchange reserves as a safety net. More specifically, China holds large exchange reserves, which were built up over time due in part to persistent surpluses in the current account, to inhibit cash inflows from trade and investment from destabilizing the domestic economy.

China’s large U.S. Treasury holdings say as much about U.S. power in the global economy as any particularity of the Chinese economy. Broadly speaking, U.S. debt is an in-demand asset. It is safe and convenient. As the world’s reserve currency, the U.S. dollar is extensively used in international transactions. Trade goods are often priced in dollars, and due to their high demand, the dollar can easily be cashed in. Furthermore, the U.S. government has never defaulted on its debt.

A Conversation with Scott Miller

Skip to another question

- 0:12 – Can China use its creditor position as an instrument of power or leverage against the U.S?

- 2:09 – Why do countries buy each other’s debt?

- 3:40 – If China sells its U.S. Treasury Bonds, what would happen? How would the economies of both countries be affected?

- 5:43 – Would countries still eagerly buy US Treasury Bonds if the US dollar was no longer the world economy’s reserve currency?

Despite U.S. debt’s attractive qualities, continued U.S. debt financing has concerned economists, who worry that a sudden stop in capital flows to the United States could spark a domestic crisis.1 Thus, U.S. reliance on debt financing would present challenges—not if demand from China were halted, but if demand from all financial actors suddenly halted.2

From a regional perspective, Asian countries hold an unusually large amount of U.S. debt in response to the 1997 Asian Financial Crisis. During the Asian Financial Crisis, Indonesia, Korea, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Thailand saw incoming investments crash to an estimated -$12.1 billion from $93 billion, or 11 percent of their combined pre-crisis GDP.3 In response, China, Japan, Korea, and Southeast Asian nations maintain large precautionary rainy-day funds of foreign exchange reserves, which—for safety and convenience—include U.S. debt. These policies were vindicated post-2008, when Asian economies boasted a relatively speedy recovery.

From a national perspective, China buys U.S. debt due to its complex financial system. The central bank must purchases U.S. Treasuries and other foreign assets to keep cash inflows from causing inflation. In the case of China, this phenomenon is unusual. A country like China, which saves more than it invests domestically, is typically an international lender.4

To avoid inflation, the Chinese central bank removes this incoming foreign currency by purchasing foreign assets—including U.S. Treasury bonds—in a process called “sterilization.” This system has the disadvantage of generating unnecessarily low returns on investment: by relying on FDI, Chinese firms borrow from abroad at high interest rates, while China continues to lend to foreign entities at low interest rates.5 This system also compels China to purchase foreign assets, including safe, convenient U.S. debt.

Who owns the most U.S. debt?

Around 70-80 percent of U.S. debt is held by domestic financial actors and institutions in the United States. U.S. Treasuries represent a convenient, liquid, low-risk store of value. These qualities make it attractive to diverse financial actors, from central banks looking to hold money in reserve to private investors seeking a low-risk asset in a portfolio.

Of all U.S. domestic public actors, intragovernmental holdings, including Social Security, hold over a third of U.S. Treasury securities. The Secretary of the Treasury is legally required to invest Social Security tax revenues in U.S.-issued or guaranteed securities, stored in trust funds managed by the Treasury Department.

The Federal Reserve holds the second-largest share of U.S. Treasuries, about 13 percent of total U.S. Treasury bills. Why would a country buy its own debt? As the U.S. central bank, the Federal Reserve must adjust the amount of money in circulation to suit the economic environment. The central bank performs this function via open market operations—buying and selling financial assets, like Treasury bills, to add or remove money from the economy. By buying assets from banks, the Federal Reserve places new money in circulation in order to allow banks to lend more, spur business, and help economic recovery.

Excluding the Federal Reserve and Social Security, a number of other U.S. financial actors hold U.S. Treasury securities. These financial actors include state and local governments, mutual funds, insurance companies, public and private pensions, and U.S. banks. Generally speaking, they will hold U.S. Treasury securities as a low-risk asset.

The biggest effect of a broad scale dump of US Treasuries by China would be that China would actually export fewer goods to the United States.

– Scott Miller

Overall, foreign countries each make up a relatively small proportion of U.S. debt-holders. Although China’s holdings have often represented around 20 percent of foreign-owned U.S. debt, China’s share of total U.S. debt has remained small. China’s holdings have steadily fallen in recent years, dropping to only about 2 percent of total U.S. debt by July 2025. That marks the lowest level since 2008.

In June 2019, Japan overtook China as the largest foreign holder of U.S. debt, and in March 2025, the United Kingdom edged out China for the number-two spot. Still, these three countries collectively accounted for just 7 percent of total U.S. debt.

It is important to note, however, that U.S. Treasury Department data on foreign debt may understate China’s true purchases of U.S. debt. The Treasury International Capital reports, which present monthly sales of U.S. debt to foreign investors, only register the initial sale, not subsequent sales, of U.S. securities. This can obscure China’s holdings within non-U.S. securities depositaries, such as Euroclear in Belgium and Clearstream in Luxembourg, and any U.S. securities held by intermediaries or proxy groups in Hong Kong, the Cayman Islands, and other tax havens.

Regardless of the exact figure that Chinese entities own, the reality is that U.S. domestic actors hold the vast majority of U.S. sovereign bonds. This is not just true for the United States. Internationally, most sovereign debt is held domestically. European financial institutions hold the majority of European sovereign bonds, and Japanese domestic financial actors hold approximately 90 percent of Japanese net sovereign debt. Thus, despite international demand for U.S. sovereign debt, the United States is no exception to the global trend.