This feature is part of a series on China-Russia relations. Click here to see other content in this series.

Russia’s war in Ukraine has cast a spotlight on the China-Russia relationship. On February 4, 2022, just weeks before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, President Xi Jinping and President Vladimir Putin met and issued a historic joint statement which stated their bilateral relationship has “no limits” and that “there are no ‘forbidden’ areas of cooperation” between them.

The two countries have indeed significantly strengthened their relationship in recent years. Chinese President Xi Jinping and Russian President Vladimir Putin enjoy close working relations, which drives high-level cooperation. The two sides also cooperate based on shared threat perceptions that the United States and its allies seek to encircle and undermine them. Close military ties and complementary economic dynamics help cement their relationship.

Yet the China-Russia relationship is complex and comes with costs for both sides. Leaders in Beijing and Moscow appear to have assessed for now that the benefits outweigh the costs, but that calculus could change. In the sections that follow, this ChinaPower feature analyzes three key weaknesses of the relationship:

- Historical and structural factors engender strategic mistrust between Beijing and Moscow;

- Russian stagnation renders Moscow a less useful partner and contributes to a growing power asymmetry; and

- Russian military aggression sparks blowback for China and exacerbates Russia’s stagnation.

Historical and Structural Factors Create Strategic Mistrust

Despite the strengthening of relations between Beijing and Moscow in recent years, considerable strategic mistrust exists between the two countries. Chinese strategic mistrust stems partly from the checkered history between the two countries, which saw the more powerful Russian Empire and the Soviet Union take advantage of a weaker China. For Russia’s part, enduring structural factors—especially geography—stoke fears that an increasingly powerful China may encroach on its interests and take advantage of Russian weaknesses. Moscow’s concerns are heightened by a strategic culture that harbors deep-seated great power ambitions and chafes at being the junior partner in a relationship with China.

The present close relationship between China and Russia is a notable deviation from history, which often witnessed the more powerful neighbor taking advantage of the weaker country. In the 19th century, the Russian Empire was party to many of the “unequal treaties” that compelled China to hand over territory, money, and other spoils to European powers. The 1858 Treaty of Aigun and 1860 Treaty of Peking were particularly harsh, forcing China to forfeit approximately 1 million square kilometers (km) of territory to the Russian Empire.

In the mid-20th century, tensions between the newly founded People’s Republic of China and the Soviet Union devolved into the Sino-Soviet Split, which lasted into the 1980s. The two countries’ longstanding border disputes were a central flashpoint of the period. In 1969, hostility along the border escalated to nuclear posturing and nearly resulted in large-scale conflict between the two communist powers. Moscow also pressed Beijing on other fronts, including criticizing Chinese repression in Tibet and indirectly calling for Tibet’s independence.

Following the normalization of Sino-Soviet relations in 1989, China and Russia officially resolved their longstanding border disputes and Moscow began expressing support or neutrality on sensitive Chinese issues like Taiwan, Tibet, and Xinjiang. Nevertheless, Moscow’s decades of antagonism have remained a source of suspicion within China. The unequal treaties that Russia was partner to were central to China’s “century of humiliation,” which the Chinese Communist Party still draws on as a source of nationalistic energy. It is impossible to de-link Russia from that legacy. Many Chinese thinkers still view these historic incidents as indicators of Russia’s willingness to use its power to pursue its own interests at China’s expense, and many in China continue to be wary of Russia’s reliability as a strategic partner.

On top of historical factors, enduring structural factors generate friction in the relationship—chief among them, geography. China’s immediate proximity to Russia leads to competitive dynamics in areas along their shared periphery, most notably in the Russian Far East, Central Asia, and the Arctic. More fundamentally, China’s immense size and power make it a daunting neighbor in the event that relations between Beijing and Moscow sour.

Following the opening of the China-Russia border in 1988, China’s presence in the Russian Far East emerged as an irritant in the relationship. As China’s economy grew, Chinese workers and businesses flowed into the region. Many went into the agricultural sector. One study found that in 2018 Chinese citizens owned or leased approximately 350,000 hectares (3,500 square km) of farming land in the Russian Far East—approximately 16 percent of the total land used for agriculture. The presence of Chinese workers in the region stirred up anger among some Russians, with many complaining about Chinese workers stealing Russian jobs and exploiting Russian natural resources.

Concerns about China’s presence in the Russian Far East have waned somewhat in recent years, and China is broadly popular among the Russian public. According to the Pew Research Center, 71 percent of Russians said they viewed China positively in 2019—the highest of all 35 countries surveyed. However, China’s presence in the Russia Far East continues to provoke negative views. A 2017 poll by the Russian Academy of Sciences found that more than one in three Russians view China's increasing presence as “expansion.” Half of respondents said that China threatened Russia's territorial integrity, and one-third of them believed that China’s policies endanger their country's economic development. This negative local sentiment has at times stalled planned Chinese investment projects, such as a Chinese-funded water bottling plant in the Irkutsk region, which was suspended after local protests in 2019.

China and Russia also face competitive dynamics in their shared backyard of Central Asia, which could become a source of tensions. Moscow remains influential in the five former Soviet states of Central Asia (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan) and it considers the region to be within its “privileged sphere of influence.” Russia has thus far been willing to accept China’s activities there, for example, by cooperating with Beijing in the Chinese-led Shanghai Cooperation Organization and by not opposing China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) ambitions. Russia currently even reaps some benefits out of China’s presence in the region: China’s considerable economic engagement there helps to facilitate regional stability and development allowing Russia to focus more on shaping military and security dynamics.

However, China is stepping up its security and economic footprint in Central Asia in ways that may increasingly be perceived through a competitive lens by Moscow. In 2021, it was announced that China would construct an outpost for police special forces in Tajikistan. While it appears that Chinese forces will not be stationed there, China’s move was seen by some as an encroachment on Russia’s ties to Tajikistan, which is a member of the Russia-led Collective Security Treaty Organization (a rough analogue to NATO comprising former Soviet states) and home to Russia’s largest overseas military base.

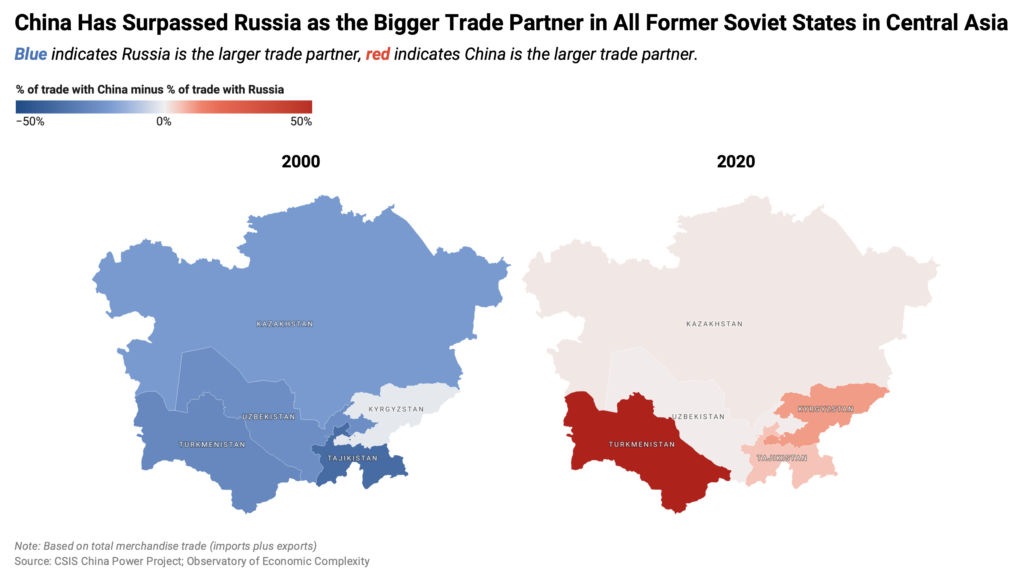

On the economic front, China has rapidly replaced Russia as the larger trading partner of all five Central Asian states. In 2000, Chinese imports from Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan totaled less than one-fourth of Russian imports, but by 2020 they were more than double Russia’s imports. China’s exports have ballooned as well, with $19.3 billion worth of Chinese goods destined for Central Asia in 2020. As this trend continues, it threatens to undercut Russia’s ability to wield its economic influence in the region.

Click to enlarge.

Finally, Russia is wary of Chinese ambitions in the Arctic, where Moscow has significant interests. Approximately one-fifth of Russia’s expansive territory is located within the Arctic Circle. This area encompasses more than 24,000 km of shoreline and is home to some 2.5 million people. Under Vladimir Putin, Russia has made the Arctic a key region of focus, including reviving Russia’s military presence there. In recent years, Russia has refurbished 50 previously closed Soviet-era military posts, including 13 air bases, 10 radar stations, 20 border outposts, and 10 integrated emergency rescue stations.

Despite lacking territory in the arctic, China has pushed to establish itself as a “near-Arctic state,” and in a 2018 white paper on the arctic, China put forward a vision for building a “Polar Silk Road” to complement the broader BRI. China and Russia have so far cooperated on energy and infrastructure projects in the region, but there have been considerable setbacks. Russia initially opposed allowing China onto the multilateral Arctic Council as an observer, and Moscow continues to be suspicious of Beijing’s strategic goals in the region. In 2012, Russia blocked Chinese research vessels from conducting surveys along the Northern Sea Route, and in 2020 Russian prosecutors charged a prominent Russian Arctic expert with treason for passing classified information to China.

In the future, Russia may feel the need to push back against China’s growing influence in these areas. In the spirit of the Chinese idiom “一山不容二虎” (one mountain cannot tolerate two tigers), China may also assert its interests over Russia’s as it pushes to shore up its regional and global power. So far, China and Russia have managed to compartmentalize competition in these areas, and they have succeeded in strengthening relations despite their turbulent history. Yet the seeds of mistrust remain planted within the relationship and could someday grow into a major impediment in the relationship.

Russian Stagnation Exacerbates Tensions

China and Russia have long sought to cast themselves as equal partners, but this narrative is increasingly difficult to maintain given the growing power asymmetry between the two. As Russia stagnates or even declines, and as China continues to bolster its national power, Russia is poised to be a less useful partner to China in countering Western influence. China’s growing lead over Russia could also exacerbate existing tensions and mistrust between Beijing and Moscow if Russia feels it is being disrespected or treated as a junior partner.

Across virtually all elements of national power—including economic, technological, and military power—China is surging ahead of Russia or rapidly catching up. Economically, China has already far surpassed Russia. On a nominal basis, the Chinese economy was nearly 10 times larger than Russia’s in 2021.1 For the first time, China even surpassed Russia in nominal per capita GDP in 2020 (though Russia remains ahead of China when adjusted for purchasing power parity). The gap is set to widen significantly in the coming years. Economic forecasts by the International Monetary Fund expect China's GDP to climb toward nearly $30 trillion by 2027 while Russia's GDP is forecasted to stall at well under $2 trillion.

Russia’s stagnating economic growth is rendering it less important as an economic partner. In 2020, Russia only accounted for about 2 percent of China’s total trade (imports and exports). By comparison, China was Russia’s largest trade partner, accounting for about 18 percent of Russia’s trade.

Long-term trends will likely render Russia even less economically relevant for China. Russia’s current value to China is in supplying energy, with oil, gas, and coal collectively accounting for two-thirds of Russia’s exports to China. Barring a major paradigm shift, Russia will decline in importance in the coming decades as China weens itself off fossil fuels. This trend is already in the works. In 2010, oil and coal made up nearly 87 percent of China’s energy consumption. In 2020, that figure had dropped to less than 76 percent. Similarly, renewable energies made up approximately 16 percent of China’s energy consumption—up from about 9 percent in 2010.

Russia would face enormous headwinds in transitioning toward a more balanced and competitive economy since Russia lags far behind China and other global leaders when it comes to technological power and sophistication. In 2020, China spent 14 times more on research and development (R&D) than Russia. This was not simply the result of differences in economic size: China also spent more than twice as much as Russia as a percent of GDP.

Across the board, Russia lacks the science and technology ecosystem needed to produce the kinds of products that would make it a more valuable and dynamic economic and technological partner for China in the long-term. The Global Innovation Index, a leading index measuring innovative capabilities and performance, ranked China 12th globally in 2021, just behind France and ahead of Japan. Meanwhile, it ranked Russia 45th alongside Vietnam (44th) and India (46th).

Russian stagnation on the economic and technological fronts is weighing on its military power, which has traditionally been a key source of its strength and influence. In 2021, Russia spent virtually the same on its military as it did in 2014 (about $64 billion). China’s military budget grew over 47 percent during that period, from $183 billion to $270 billion.2

This has multiple implications for China. In recent decades, Beijing has looked to Russia as a major military partner in competing with the United States and its allies, but Russia’s faltering defense spending is weighing on China and Russia’s collective capacity to compete militarily. In 2021, the United States and its NATO and Indo-Pacific allies collectively spent 3.7 times more on defense than China and Russia. More concretely, Chinese experts have complained about the state of the Russian military, highlighting, for example, that the Russian naval fleet largely comprises outdated Soviet-era vessels and equipment.

It is unclear whether, or at what point, the power disparity between the two countries would threaten their relationship. If Russian power wanes and Western isolation of Russia continues, Moscow may conclude that it has no choice but to bandwagon with China. However, given Russian perceptions of itself and its history as a great power, Russia may be unwilling to have a close partnership with China that is not built on equality.

There are signs that some Russians are already wary of being treated poorly by China. In March 2022, former Russian Foreign Minister Andrei Kozyrev described China’s leaders as “ruthless businessmen” and said “China will never take [Putin] as an equal partner or even as ally." If Russian leaders feel that they are being taken advantage of or treated like the junior partner, they may ultimately choose to cool relations with Beijing and limit cooperation. Russia may even assess at some point that the power imbalance has become so severe that China poses a direct challenge or threat to Russia, which could result in a full pivot away from China.

Russian Aggression Runs Counter to Chinese Interests

Compounding these issues is Russia’s persistent military aggression on the world stage. Russia’s numerous military interventions—especially its ongoing war in Ukraine—have created political and economic blowback for China. On top of that, Russia’s war in Ukraine has weakened Russia, diminishing its utility to China and further exacerbating the widening power gap between China and Russia..

Chinese strategists and analysts have contrasted Russia’s willingness to use force with China’s forbearance. Some have described Vladimir Putin as a “revolutionary” seeking to overturn the existing international order and noted that Moscow’s goals render it more willing to use violence to advance its interests. By comparison, Chinese scholars have characterized China as having the more modest goal of rendering the existing international system more conducive to China’s growth and development—and therefore less willing to resort to force.

Russia’s willingness to use aggression has put China in politically awkward situations. Chinese officials have long described territorial integrity and non-interference in the internal affairs of other countries as a cornerstone of China’s foreign policy. Chinese officials and propaganda outlets frequently try to cast China as having never invaded or bullied other countries. Russia’s repeated invasions of other countries run in direct opposition to those principles.

China has at times gone so far as to subtly criticize Russian military aggression. In 2008, then-spokesman of China’s foreign ministry Qin Gang stated that China “expressed concern” over the situation in Abkhazia and South Ossetia during Russia’s war in Georgia. Mostly, China has sought to neither criticize nor directly side with Russia. Beijing, for example, has not recognized the independence of Abkhazia and South Ossetia from Georgia; nor has it recognized the breakaway Ukrainian territories of Donetsk and Luhansk or Russian claims over Crimea.

In the case of Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, Xi Jinping has gone farther by publicly legitimizing Russian security and sovereignty concern, but this has come at a political and diplomatic cost. In the United Nations, China was compelled to make unpopular votes that placed it among a small minority of countries. In March 2022, for example, 141 countries voted in the UN General Assembly in favor of a resolution condemning Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, while China joined a minority of 34 other countries in abstaining.

Russia’s war in Ukraine has also propelled a rapid and significant improvement in relations between the United States and its European allies as they collectively counter Russia, and it has strengthened perceived fault lines between democracies and autocracies—unwelcome outcomes for China. In the United States, China’s tacit support for Russia has brought a spotlight to the China-Russia relationship, with 62 percent of people polled describing it as posing “a very serious problem.” In Europe, a key economic partner for China where Beijing has been pushing to gain influence, countries there have toughened their stance toward China. In April and May, China sent an envoy to meet with officials in eight central and eastern European countries with the hopes of improving ties, but China’s outreach was rebuffed.

The war in Ukraine has also inflicted economic pain on China. The global rise in energy prices sparked by the war led oil prices to spike in China—much as they did in other countries. According to Chinese customs data, the price of China’s crude oil imports rose to RMB 5,070 per metric ton in April 2022—up 37 percent from January 2022.

China and its companies are also facing the added burden of navigating Western sanctions on Russia. While China has not joined U.S. and European sanctions on Russia, and despite Beijing’s calls for companies to continue conducting business in Russia, many Chinese firms have paused or cut operations there. This includes major Chinese tech companies like computer-maker Lenovo, smartphone-maker Xiaomi, and drone-maker DJI.

As a result, China’s exports to Russia plummeted to RMB 24.1 billion in April 2022—down 53 percent from the recent high of RMB 52 billion in December 2021. Technology exports have been particularly hard hit. In March, laptop sales to Russia were down more than 40 percent and smartphones down by nearly two-thirds. In late May, five Chinese firms were told to stop construction of a Chinese-Russian liquefied natural gas pipeline, a key node in China’s “Polar Silk Road,” to avoid EU sanctions.

In addition to causing political and economic blowback, Russia’s wars threaten to further diminish Russia’s utility as a strategic partner for China. Russia’s 2014 invasion of Ukraine created significant setbacks for the Russian military and its supporting defense industry. The war disrupted Russia’s ability to deliver weapons systems to Vietnam—one of Russia’s top arm export markets—which in turn contributed to a broader decline in Russia’s arms exports in recent years. During the 2016-2021 period, Russian arms sales around the world declined 24 percent over the previous six-year period, and its share of global arms sales fell from 25 percent to 19 percent. This undercut a notable benefit of the China-Russia relationship for Beijing, wherein Russia could wield its prominence as an arms exporter to influence countries—like Vietnam—with which China has tense relations.

Russia’s latest invasion of Ukraine has had far more drastic consequences for Russia. Western sanctions have had substantial impacts on the Russian economy. Russia’s GDP is expected to shrink by 8.5 percent in 2022 and unemployment is expected to rise substantially. Russia’s military losses in Ukraine are also staggering. In June 2022, U.S. Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Mark Milley stated that the Russian military had already lost roughly 20 to 30 percent of its armored force in Ukraine, which he described as a “huge” and “significant” loss.

For now, Beijing has chosen to double down on its relationship with Russia despite these drawbacks. These developments nevertheless represent meaningful headaches for China. Russia is stagnating, and perhaps in outright decline, which could ultimately exacerbate existing mistrust between Beijing and Moscow and potentially render Russia of far less strategic value to China.