By: Bonny Lin, Brian Hart, Truly Tinsley, and Leon Li

January 13, 2026

The year 2025 was a tumultuous period for U.S.-China relations. Tensions spiked repeatedly amid a heated trade war, as well as over key geopolitical flashpoints like Taiwan. Relations stabilized somewhat after President Donald Trump and President Xi Jinping concluded a series of trade and economic agreements in late 2025, but major questions remain about the status and future outlook of the relationship.

To shed light on these issues, the CSIS China Power Project surveyed dozens of former U.S. government officials and leading China experts. The online survey was fielded from December 1–18, 2025, and received responses from 79 individuals.1 The survey and this summary report are divided into four sections: the overall U.S.-China relationship, economics and trade, diplomacy and geopolitics, and military and security.

The tiles below highlight the survey’s most important takeaways. Click a tile to jump to that specific section of the report.

Overall U.S.-China Relations

The survey began by taking stock of where the U.S.-China relationship stands at the end of 2025 and asking experts to forecast the overall trajectory of the relationship in 2026.

U.S. experts were first asked to evaluate China’s view of the United States. Unsurprisingly, none of the experts think that China views the United States as a close partner, and only 5 percent of experts feel that China views the United States as a “normal partner with which to cooperate and compete” (see figure 1).2 Experts see the relationship more pessimistically than that.

Yet experts were divided on just how negatively China views the United States. About half say China sees the United States as a “strategic competitor,” while almost as many believe China views the United States even more negatively as an “adversary.”

Next, the survey sought to gauge experts’ views on where the relationship stood as of December 2025—nearly one year into President Trump’s second term. Only 26 percent of experts strongly agreed or somewhat agreed that U.S.-China relations are more stable than they were a year ago, while 18 percent of experts neither agreed nor disagreed that relations are stable (see figure 2).

A slight majority (57 percent) strongly or somewhat disagree that U.S.-China relations are more stable than they were a year ago. This breakdown indicates a surprising spread of views on even the nature of current U.S.-China relations.

These mixed views may stem from uncertainty over the fate of the agreements that President Trump and Xi made in their meeting in Busan, South Korea. That meeting produced several results, including agreements to reduce tariffs, Chinese commitments to resume purchases of U.S. soybeans and other agricultural products, temporary suspensions of the U.S. 50 percent “Affiliates Rule” on export controls and China’s most severe rare earth export controls, and agreements on other areas.

Just over half of the experts polled think that both sides will make efforts on some of their commitments but fall short on other commitments, but 34 percent believe that neither side is likely to meet their commitments (see figure 3). Only 3 percent (one respondent) feel confident that both sides will keep all their commitments.

The experts were much more skeptical that China would keep its commitments: none of the respondents believe that Beijing will meet its commitments while Washington keeps its commitments, but 13 percent believe that the United States will likely meet its commitments while China does not. This may stem from past experience, most notably China’s failure to meet the commitments it made as part of the Phase One trade deal during the first Trump administration. As part of that deal, China agreed to increase purchases of certain U.S. goods and services by $200 billion over 2020–2021 compared to 2017 baseline levels. However, China fell well short of that, purchasing only 58 percent of the U.S. goods and services exports that it had committed to purchase under the deal.

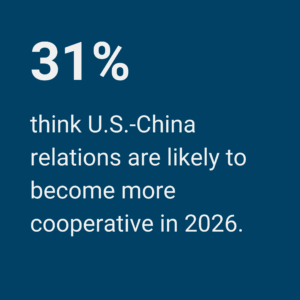

The uncertainty over the fate of this deal appears to loom large over the fate of the overall U.S.-China relationship in 2026. Experts are deeply divided in their assessments of the trajectory of the coming year.

About one-third of experts think the relationship is likely to become more antagonistic, while another one-third of experts predict that the relationship will become more cooperative (see figure 4). The remaining one-third assesses that the relationship will stay about the same. Overall, the vast majority of the respondents think it is unlikely that the relationship will change drastically in one year, with only about 8 percent of experts predicting the relationship will become either much more cooperative or much more antagonistic.

Economics and Trade

Economics and trade issues dominated U.S.-China relations in 2025. The tit-for-tat trade war showcased the different areas of leverage and vulnerabilities on both sides. The questions in this portion of the survey sought to understand China’s strategy in the trade war, gauge the effectiveness of its approach, and understand China’s limitations.

The first question asked experts about the motivations behind the measures China took in approaching trade and tariff negotiations with the United States. About 27 percent of respondents answered that they felt Beijing pursued a primarily offensive strategy in dealing with Washington (see figure 5). Less than 10 percent said China’s strategy was mainly defensive in nature.

The lion’s share of respondents (about 65 percent) assessed that China’s strategy incorporated both offensive and defensive measures. This suggests that in some cases China appeared to be responding in kind to measures taken by the Trump administration, while at other times Beijing sought to gain an upper hand in negotiations with Washington.

The most significant economic weapon China wielded against the United States was undoubtedly its chokehold over rare earths—a group of minerals that are critical to numerous industries.

China controls about 69 percent of global rare earth mining production and 92 percent of processing, as well as 93 percent of rare earth magnet manufacturing. In October 2025, China ratcheted up its export controls on rare earths to unprecedented levels. Under those rules, foreign firms were required to obtain licenses to export items containing even trace amounts of Chinese-origin rare earth materials, or that were produced using Chinese equipment or technologies. Most importantly, these rules applied to firms exporting goods between countries that did not pass through China’s borders, marking the first time China utilized extraterritorial rules akin to the U.S. foreign direct products rule.

Left in place, these restrictions could have imposed significant pain on U.S. and other countries’ companies across a wide range of industries. However, China suspended the rule for a year as part of the agreement reached between Trump and Xi in Busan.

When asked to assess how China used rare earth export restrictions as a negotiating tool, over two-thirds of experts responded that China “played its hand well,” a clear sign that it was effective (see figure 6). Only 23 percent of experts said China “overplayed its hand” in leveraging rare earths.

Those who believe China “overplayed” its hand generally assert that China’s rare earth restrictions showcased Beijing’s willingness to use coercion and pushed vulnerable countries closer to the United States. In the days leading up to the Trump-Xi meeting in Busan, the United States concluded agreements and memorandums of understanding relating to rare earths and other critical minerals with Australia, Cambodia, Japan, Malaysia, and Thailand—showing the Trump administration’s efforts to reduce China’s leverage.

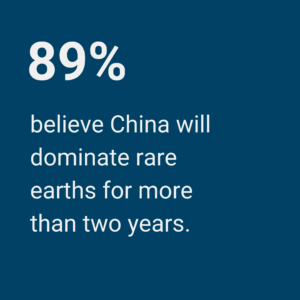

However, reducing reliance on China will take time. In this survey, 52 percent of experts said China may be able to wield its dominance over rare earths for up to five more years (see figure 7). Another 30 percent said China could wield its influence in the industry for more than 10 years, and some felt it could take even longer to break China’s dominance. Only 11 percent of experts said China’s dominance over rare earths and other critical minerals could be ended in the next one to two years.

While China has areas of economic leverage, it also faces considerable challenges. China is struggling with significant domestic economic headwinds stemming from a slowdown in its real estate sector, sluggish domestic consumption, and ballooning levels of government debt.

When asked whether this economic slowdown impacts China’s foreign policy, 80 percent said it had some impact, but there was no consensus on what that impact is (see figure 8). About 51 percent said China’s economic challenges will cause China to act more assertively in some areas and exercise more restraint in others. Another 19 percent believe it will cause China to act with more restraint, while 10 percent believe it will cause China to act more assertively.

Diplomacy and Geopolitics

The third section of this expert survey focused on China’s foreign policy and major geopolitical issues.

The issue of Taiwan is always at the core of China’s foreign policy and engagements with other countries—especially U.S.-China relations. In 2025, there was speculation that President Trump might be willing to make policy changes on Taiwan as part of a broader deal with China, and some believed that the Trump administration was constraining engagements with Taiwan to avoid derailing trade talks with China. In June, a meeting between Taiwan’s defense minister and U.S. Pentagon officials was canceled, and in July the Trump administration reportedly denied a request by Taiwan’s President William Lai for a stopover in New York while en route to Latin America. Reports from September 2025 also indicate that the administration rejected a roughly $400 million military aid package for Taiwan ahead of Trump’s October meeting with Xi Jinping (though the administration later approved a record-breaking arms sales package later in the year).

In light of these developments, the survey asked experts to assess whether China believes it can negotiate or pressure the United States to change U.S. policies toward Taiwan. An overwhelming 77 percent responded that Beijing believes the United States would be willing to make some concessions on U.S. policy (see figure 9). Of these, 24 percent believed China thinks Washington might make major concessions on Taiwan, while 53 percent said Washington would only be willing to make minor concessions. Only 10 percent of experts thought China assesses that the United States is unwilling to negotiate any changes to its Taiwan policies.

Beyond Taiwan, one of the biggest geopolitical developments for China in 2025 was a diplomatic row with Japan when China sought to pressure the new Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi to retract comments she made related to Taiwan. Takaichi had remarked to Japanese Diet that “warships with the use of military force” against Taiwan could lead to a “survival-threatening situation” for Japan. Beijing interpreted those comments as highly provocative because they suggest that the Japan Self-Defense Forces would be legally allowed to engage in collective self-defense activities that could support U.S. intervention in the event of a conflict over Taiwan. China responded with a range of diplomatic barbs, economic punishments, and military activities aimed at intimidating Tokyo.

This survey asked experts how they assess China’s willingness to escalate against Japan. About 71 percent of respondents answered that China’s escalation would be moderate (rather than significant), but they disagreed on whether China’s actions might last more or less than a year (see figure 10). A plurality assessed that China would be willing to act for longer than a year. Only about 30 percent of the respondents answered that China would escalate significantly (for either more or less than a year).

Another key area of focus for China is the Global South, where Beijing is pushing to deepen its influence. The survey asked experts to assess where in the Global South China is likely to make the most gains over the next three years (i.e., during the Trump administration). Respondents were able to select up to two regions, and Africa proved to be the most commonly picked region, with 57 percent of responses including Africa, followed by Southeast Asia, which was included in 38 percent of all responses (see figure 11).

Notably, Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) was the third-ranked region, despite the fact that the Trump administration has made clear it is prioritizing the LAC and broader Western Hemisphere. The administration’s 2025 National Security Strategy lists the Western Hemisphere first among the regions to prioritize, and it lays out a “Trump Corollary” to the Monroe Doctrine as the framework that will guide U.S. relations in the Hemisphere.1 Under this framework, the United States has stated it will “deny non-Hemispheric competitors the ability to position forces or other threatening capabilities, or to own or control strategically vital assets” in the Western Hemisphere. Shortly after the National Security Strategy was released, China issued its third policy paper on Latin America and the Caribbean, in which it showcased its ambitions to further increase cooperation with the region.

Finally, this section of the survey sought to capture experts’ views on China’s cooperation with Russia, Iran, and North Korea—a group collectively referred to by various names, including “CRINK,” the “axis of upheaval,” and others. Concern has risen among policymakers in Washington over the collective threats this group may pose to U.S. interests and global governance, especially given their growing cooperation in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

When asked to weigh in on their concerns about CRINK, respondents’ answers varied considerably. A slight majority (56 percent) was somewhat or very concerned (see figure 12). Of these, only 10 percent say they are very concerned and believe that the four countries are “de facto allied against the United States.” A plurality (46 percent) believed CRINK poses a considerable threat but did not go as far as saying the four are allied against the United States. Another 38 percent of respondents said CRINK cooperation poses only a “minor threat,” and the remaining 6 percent said CRINK poses no clear threat.

Military and Security

The fourth and final section of the survey focused on military and security developments—issues that have become significant challenges to U.S.-China stability and peace and security in the Indo-Pacific.

As China’s military power has grown, Beijing has become more willing to use the PLA to intimidate its neighbors, including U.S. allies and partners. In recent years, Chinese and Philippine fishing, law enforcement, and naval vessels have engaged in repeated tense confrontations in the South China Sea involving water cannons, collisions, and sometimes injuries. Cross-Strait relations have continued to deteriorate as well, with the PLA holding around two or three named, large-scale exercises around Taiwan each year. China also engaged in dangerous military activities against Japan following Takaichi’s statement on Taiwan in late 2025, including Chinese fighter jets locking radar on Japanese aircraft. Meanwhile, China and India have had deadly confrontations along their disputed border over the last several years. While the two countries have made progress toward lowering tensions lately, new flashpoints could emerge between the two Asian giants.

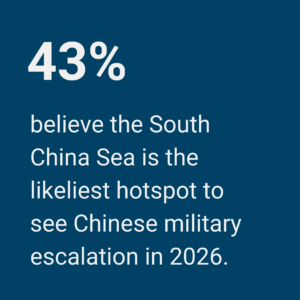

To get a high-level view of security dynamics in the region, the survey asked experts to assess where in 2026 they see the highest risk of Chinese military escalation, either intentional or accidental. About 43 percent of experts named the South China Sea as the most likely hotspot for Chinese escalation, followed by 33 percent saying the Taiwan Strait (see figure 13). This might be because China views the Philippines as less militarily capable than Taiwan, and a crisis or conflict in the South China Sea is unlikely to lead to a high-intensity kinetic war like one over Taiwan. China may also perceive that the United States is less focused on the dynamics in the South China Sea.

Other flashpoints besides the South China Sea and Taiwan were seen as much less likely locations for PLA escalation. Among the remaining ones, the disputed Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands were named as most likely, which is unsurprising given the recent tensions between China and Japan.

While experts may assess that the South China Sea is a more likely military flashpoint than the Taiwan Strait, that does not mean they think the risk of war over Taiwan is decreasing. In fact, experts in this survey see the risk of a war over Taiwan rising.

About 41 percent of respondents said that the risk of a U.S.-China military conflict over Taiwan is higher over the next three years compared to one year ago (see figure 14). In contrast, only 24 percent say the risk of war is lower over the next three years. The remaining 35 percent see no change in the likelihood of a war.

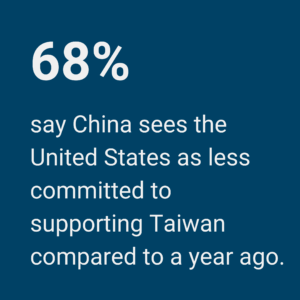

A crucial variable in deterring a Chinese attack on Taiwan is whether the United States comes to Taiwan’s defense. The survey asked participants about this issue and found that a majority of experts believe China sees the United States as less committed to Taiwan’s defense now compared to a year ago.

About 68 percent of respondents agree (either somewhat or strongly) that, compared to a year ago, China believes that the United States is now less committed to supporting and defending Taiwan (see figure 15).

Another crucial issue related to Taiwan’s security is whether and how China’s partners might support China in a conflict. China has established deep security ties with Russia, especially in the wake of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022. Since then, China has doubled down on its relations with Russia by sustaining its economy with increased volumes of trade and supplying dual-use goods that support Russia’s war efforts in Ukraine. China has also acted in unity with Russia on many diplomatic initiatives and in multilateral settings, and China has leveraged joint military exercises with Russia to deter and intimidate their shared adversaries.

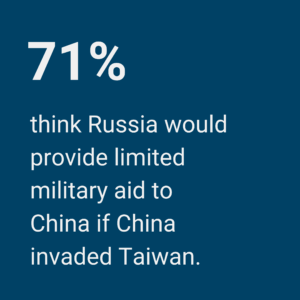

The survey sought to understand whether and how Russia might be willing to support China in a conflict over Taiwan. All experts assume Russia would provide political and diplomatic support to Beijing if China invaded Taiwan, and almost all (84 percent) also believe Russia would provide economic support. About 71 percent of the experts also believe that Russia would provide limited military aid to China, such as intelligence sharing, offensive cyber operations, and arms transfers. However, only one respondent believes that Russia would be willing to directly intervene by deploying its military forces into the conflict.

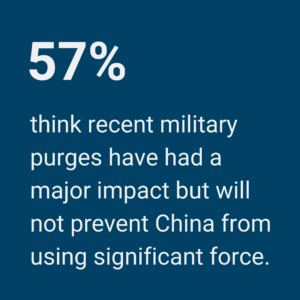

Finally, the survey sought to understand how ongoing issues within the PLA could impact Beijing’s willingness to use force in the near term. In recent years, Xi Jinping has intensified his anti-corruption and loyalty campaigns within the military, purging dozens of senior leaders within the PLA and the Chinese defense industry. The scale of this campaign could be seen at the Chinese Communist Party’s Fourth Plenum in October 2025, one of the year’s most important party gatherings. Among the 42 military-affiliated party Central Committee members, only 15 attended the Fourth Plenum. Of the 27 absentees, eight have already faced disciplinary actions and twelve have been rumored to be under investigation. Xi’s purges have even targeted members of the Central Military Commission, the pinnacle of the PLA’s leadership. Four members of the commission have been purged recently, including one of its vice chairmen, He Weidong, the top political commissar Miao Hua, and former defense ministers Li Shangfu and Wei Fenghe.

The purging of top-ranking generals and military commanders has raised questions about the PLA’s combat readiness and effectiveness. In the survey, only 13 percent assessed that the purges had undermined readiness to the extent that it would prevent China from using significant military force in the next two years. A majority (about 57 percent) say that the purges have had a major impact but will not prevent China from using significant force. This likely indicates that most experts assess that decisions on the use of force will be made based on political and strategic necessities, not on PLA readiness.

Survey Methodology

For this survey, the CSIS China Power Project reached out to dozens of former U.S. government officials and leading China experts in the United States and received responses from 79 participants. The survey included 17 questions divided into four key areas: the overall U.S.-China relationship, economics and trade, diplomacy and geopolitics, and military and security. The survey also included three demographic questions to help understand the breakdown of respondents. CSIS fielded the survey in an online form from December 1–18, 2025.

A majority of the 79 respondents have over 20 years of experience in the field and have proficiency in Mandarin Chinese. Their expertise also covers a wide range of topics, including economics and technology, Chinese domestic politics, international relations, and defense and security.

For the full text of the survey, click here.