Innovation is a primary source of national power. A country’s ability to develop new products and methods of production enables it to create the goods desired by others. In turn, innovation creates wealth, leads to technological advancement, and fosters further innovation through the development of derivative products.

One way to measure innovation is through intellectual property (IP) protection in the form of patents. Patents secure exclusive rights to an invention and thereby offer insight into key areas of innovation. This ChinaPower feature assesses the relationship between patents and innovation by exploring trends in patent applications by Chinese inventors at various patent offices, examining the surge in domestic patent applications in China, and considering the relative value of patents.

Why Patent Families Matter When Comparing Countries

In 2021, the China National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPA) processed 46.6 percent of all patent applications in the world. With nearly 1.59 million total applications, China’s patent office processed 268 percent more applications than the United States’ office and 548 percent more applications than Japan’s that year. This amounts to a massive thirty-fold increase since 2000, when China’s patent office processed less than 52,000 patents.

While the explosion of domestic patent applications in China is impressive, this growth does not necessarily correlate directly with dramatic advances in innovation. Comparing patent applications and grants between countries does not take into account differences in government policies and the domestic regulatory environment.

In the case of China, the CNIPA established the National Patent Development Strategy for 2011 to 2020 to explicitly equate patent generation with innovation and to call for government incentives to bolster the number of domestically filed patents. This strategy resulted in many CNIPA patents being awarded for small design tweaks and incremental changes rather than entirely new inventions.

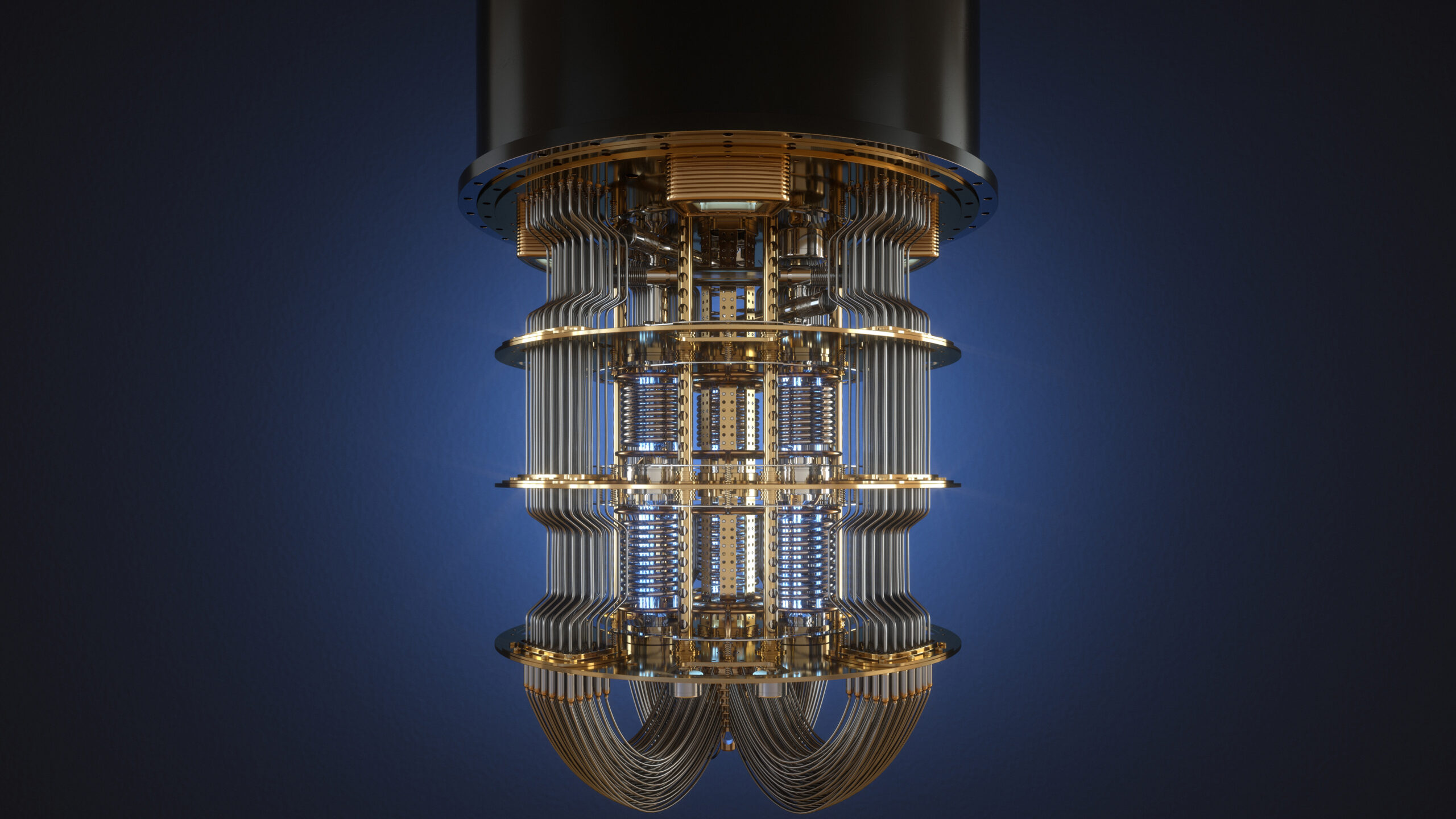

Patents provide insights into China's progress in cutting-edge fields like quantum technology. Explore our feature to learn more.

Given the nuances of domestic filing procedures, it is necessary to examine how Chinese patents fare internationally at the world’s top patent offices. Patent families offer a means to assess patent quality across borders and explore what these patents reveal about innovation. In general, patent families consist of a collection of documents filed at different patent offices around the world for the same invention.

Although several different patent families exist, the triadic patent family is widely recognized as the gold standard. Triadic patents are filed jointly with authorities in the largest global technology markets: the Japan Patent Office (JPO), the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO), and the European Patent Office (EPO). Joint filing guarantees broader intellectual property protection and offers greater opportunity for a specific technology to generate revenue for its inventor on the global market. However, this protection comes at a cost: triadic patent applications are considerably more expensive than domestic applications. They are harder to obtain, and in some cases, can take up to five or six years to process.

China lags well behind the United States and Japan with respect to triadic patents. According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), China only had 5,897 triadic patents in 2020. By comparison, the United States had 13,040 triadic patents and Japan had 17,469 in the same year.

A key reason for this disparity is that Chinese residents largely file domestically. In 2021, Chinese patent seekers filed 92.7 percent of their patent applications domestically through the CNIPA, and only 7.3 percent of Chinese applicants filed abroad. In contrast, 48.6 percent of U.S. applicants and 46.1 percent of Japanese applicants filed abroad. This suggests that while China now processes the greatest number of domestic patent applications annually, many of these patents do not hold up under the more stringent requirements of the international patent system—or that Chinese inventors are less willing or able to take extra steps to protect their IP abroad.

Besides triadic patents, another area worth evaluating is filings through the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT), a multilateral framework that facilitates easier joint filing for patents in a number of countries. Here, China has progressed significantly. China signed on to the treaty on January 1, 1994. According to the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), Chinese applications for PCT patents increased from 782 in 2000 to 69,604 in 2021. China has been the global leader in PCT application volume since 2019 when it passed the United States, ending decades of U.S. dominance in PCT filings.

Importantly, however, PCT applications are not tantamount to actually holding an overseas patent. They only provide limited, temporary patent-pending status, which can help make it easier to eventually file patents. Chinese inventors pursuing PCT applications will still have to carry through with filing patents in other markets to gain full overseas IP protections.

Ultimately, China still lags other countries in terms of its global IP reach. Yet it is possible that the standard U.S.-EU-Japan triad could shift to include the CNIPA as a leading patent office. In 2021, the CNIPA alone received more patent applications than the combined total of the next 12 largest patent offices, including the USPTO (591,473), JPO (289,200), EPO (188,778), and the Korean Intellectual Property Office (KIPO, 237,998). Among the top five IP offices for patent applications, only China’s office saw double-digit growth between 2011 and 2021—other offices saw stagnating or declining rates of applications.

Comparing Patent Quality

Not all patents are equal. Even in cases where the legal framework to acquire and maintain patents is similar, differences in the value of patents still persist. Notably, the proliferation of low-quality patents may hinder innovation as it increases barriers to entry. One metric used to gauge the value of a specific patent is its number of citations.

Patents include citations to relevant scientific data as well as previous patents that were deemed important to the creation of the newly patented product. As a secondary effect, patent citations reveal the relative influence and reach of individual patents. As such, how much a specific patent influences the development of other technologies can be extrapolated from its frequency of citations.

For example, a patent for a new toothbrush might be cited by its derivative successor, or by no one, while a patent for a semiconductor used in a variety of electronics might be cited in hundreds of different patent papers. In this case, the number of citations suggests the relative importance of the product in terms of its contribution to innovation within a specific market.

A second measure of patent value can be derived by looking at how patent owners seek to protect their intellectual property in international markets. A study by Eberhardt, Helmers, and Yu examined how many Chinese firms have sought patent protection with the USPTO as well as the CNIPA. USPTO protection requires a greater degree of confidence in both the strength and uniqueness of an innovation to pursue protection, thereby revealing whether a patent filed domestically in China would stand up to international standards.

Furthermore, foreign patent recognition signifies market ambitions beyond the domestic sphere, which can also indicate the relative value of a product. The relatively limited number of Chinese patents filed with the USPTO are held by a few large, export-oriented firms in the computer, communication, and consumer electronics industry.

Finally, Chinese patents have noticeably shorter shelf lives compared to those of advanced economies. In general, patents with longer lifespans are considered to be more valuable as holders only choose to pay recurring maintenance fees if the patent is still worth upholding. A comparison of patent lifespan between Germany, the United States, and China found that between 2007 and 2015, Chinese patents averaged seven years in service. U.S. patents saw 10 years of use while German patents had nearly double the lifespan of a Chinese patent at 12 years. The low retention rate of Chinese patents implies that despite the large volume of patents being granted in China, most are being awarded to comparatively less valuable innovations with limited staying power.

China's Evolving Patent Landscape

By many different metrics, China’s past patent output has been heavily geared toward quantity, and has not necessarily coincided with improvements in quality. However, there are signs that this is changing as China makes substantive progress toward producing innovative and cutting-edge products.

The rapid rise of Chinese patents in recent years has been supported by several Chinese policies that encourage domestic innovation. One of the most prominent of these has been Xi Jinping’s Made in China 2025, which aims to upgrade key domestic industries to compete with advanced economies in high-tech sectors.

The outcomes of this strategy can be seen by comparing corporate patents from a global perspective. According to WIPO, the Chinese telecommunications giant Huawei was the top PCT applicant between 2019 and 2021, followed by Samsung (South Korea), Qualcomm (U.S.), and Mitsubishi (Japan). Two other Chinese technology companies, Oppo and BOE, ranked in the global top-10 as well. The emergence of Chinese companies is a recent development as neither Huawei nor Oppo Mobile ranked in the top-100 for worldwide corporate patent applications until the 2000s.

Yet a deeper look shows that certain government policies have been emphasizing quantity over quality. By filing for patents, Chinese companies can receive cash bonuses, subsidies, and even lower corporate income taxes from the government. Huawei, for example, has offered patent-related bonuses to employees—a practice that some experts have assessed as lowering the quality of China’s patent applications.

However, Beijing is ramping up measures to promote innovation that could spur higher-quality patent output. The Chinese government has put in place tax incentives to promote research and development (R&D), a critical ingredient for innovation. Chinese spending on R&D has surged in recent years. According to official Chinese figures, spending on R&D rose to $456 billion in 2022, marking a 10.4 percent increase from the previous year.1

Authorities are also overhauling elements of the country's IP system. China’s 14th Five Year Plan, which lays out the country’s priorities and goals during the 2021–25 period, states that the government will “optimize patent subsidy and incentive policies” to “better protect and incentivize high-value patents and cultivate patent-intensive industries.” In line with this, in 2021, Chinese authorities released an outline for transforming China into a global “intellectual property power” (知识产权强国) by 2035. The outline strongly emphasizes that both a large quantity and high quality of IP protections are needed to achieve “intellectual property comprehensive competitiveness” that “will rank among the top in the world.” To realize this, the outline calls for streamlining the nation’s IP management system to increase efficiency, focusing on IP protection in emerging technologies, and encouraging innovation and talent across society.

In a significant move, the CNIPA issued a notice in 2022 that financial incentives for patent licensing should be reduced by at least 25 percentage points every year until they are entirely cut by 2025. The CNIPA has also proposed and implemented several changes to its patent law including stricter examination guidelines, especially for utility model patents.

Steps such as these may pay off. By some measures, China’s patents are already making headway in terms of being higher quality. Throughout the 2000s, foreign applicants accounted for the majority of invention patents being filed in China, which indicated the relative lack of innovativeness of China’s own domestic inventors compared to their foreign counterparts. In recent years, however, this trend has been completely reversed. In 2022, only 12.9 percent of the invention patents granted by the CNIPA went to foreign applicants.

Taken together, these trends show that China’s rapid rise over the last two decades has been tilted toward quantity over quality. Yet recent developments suggest that Beijing is increasingly prioritizing quality-oriented patents and innovation, and making progress on these fronts.